From Museums and Interactive Multimedia: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of the MDA and the Second International Conference on Hypermedia and Interactivity in Museums, ICHIM 1993. Cambridge, England, 20-24 September 1993. Archives & Museum Informatics, Pittsburgh, PA, USA 1993

Abstract

However this pairing of experience level and type of presentation is based on three flawed assumptions. The first is that visiting a museum is about the getting of knowledge (i.e. the cognitive domain) (1). The second is that linear systems (or presentations) are best suited to affective experiences, whereas non-linear systems are best suited to cognitive processes. The third is that every visitor, from novice to scholar, knows at least how to “look” at an unfamiliar object or image.

This paper counters these assumptions and argues that the most important outcome for a museum to achieve is a personal engagement between an exhibit or exhibits and the novice visitor. Unless this occurs, the visitor will at best never progress to any higher levels of understanding or at worst never return!

Engagement is a process that begins with the visitor’s experiences and interests in ways that ”tap into” feelings in a non-threatening way. These principles, as exemplified in live interaction, can be applied also to computer-based interactives. Examples are given of how this can be achieved in practice.

The delivery of educational services to non-expert museum visitors can be divided into five broad methods:

- Exhibits and labels arranged in such a way as to “tell a story” (in art museums, usually an art-historical story).

The disadvantages of this method (the so-called “straight” exhibition) should be fairly obvious: It makes sweeping assumptions about the visitor’s ability to grasp the logic of an exhibition layout and to make comparisons and conclusions without assistance. - Exhibits and labels, supported by extended labels and explanatory panels.

This method is only a slight improvement on the first. It assumes that the visitor only needs, apart from access to the exhibits, some background information, e.g. “Rembrandt was a miller’s son”, or “Igneous rocks are formed by plutonic activity.” - Talks and discussions with small groups of people in front of exhibits — “floor-talks” (sometimes called “guided tours”).

- Slide lectures delivered in a museum theatre, prior to viewing of exhibits.

These two methods are similar, except that in the latter there is no immediate access to the physical exhibits. As partial compensation however, related material not otherwise available on the museum floor — such as images from other sources and segments of film or video — can be utilised. - Exhibits and labels, supported by interactive exhibits (including computer-controlled multimedia).

The interactive exhibit, as for the previous two methods, at least has a chance of meeting the needs of non-expert visitors because it can adapt to some of their responses. In fact it can be the nearest substitute to a real, live museum educator.

Among the advantages of interactive exhibits (or hypermedia) over “live” methods are:

- (Murphy’s law aside) availability to the general public during the entire opening hours of the museum, at a reasonable long-term cost, and

- more or less instant access to a wide range of related material — such as still and moving images, and sound.

Although the terms “hypermedia” and “hypertext” imply the free, unstructured exploration of an idea-space, many practical applications of it more closely resemble very smart reference books — that is, vast amounts of information presented so that any specific topics or issues can be explored in depth if desired. The underlying assumption is that the information is always arrived at convergently, that is, from the general to the specific.

Smart reference book = “work”

Hypermedia, treated in this way, is clearly not for the novice visitor, but rather for the scholar or the connoisseur: ‘It has been suggested, with some reason, that hypermedia is more suitable for advanced learners than novices, because it reveals the complex interconnectedness of information, and requires judgemental skills to navigate through the information in a meaningful way … But simpler interactive programs, designed for well structured knowledge domains, can serve novices.’ — Alsford (1991), p. 10; Huston (1990), p. 338. “After all,” the argument would go, “the novice visitor, not having an overall grasp of the field to which the exhibits relate, could not know what possibilities there are to explore and would probably suffer from cognitive (over)load” — see Oren (1990), pp. 127–135).

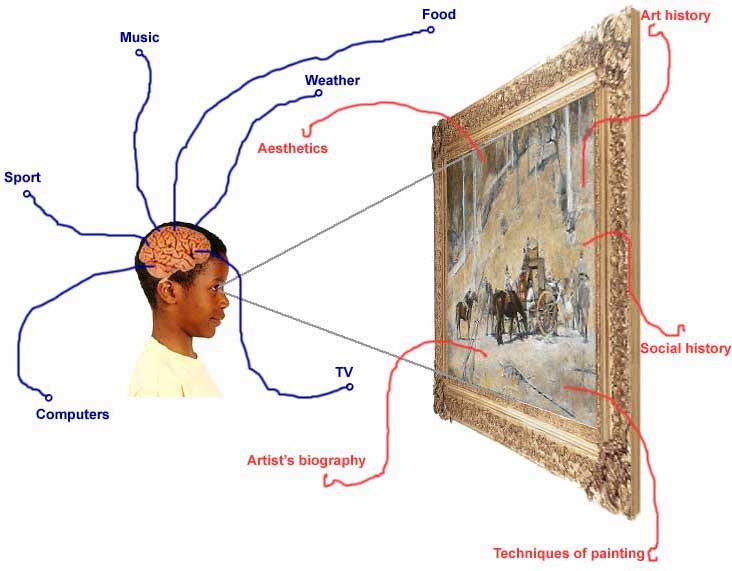

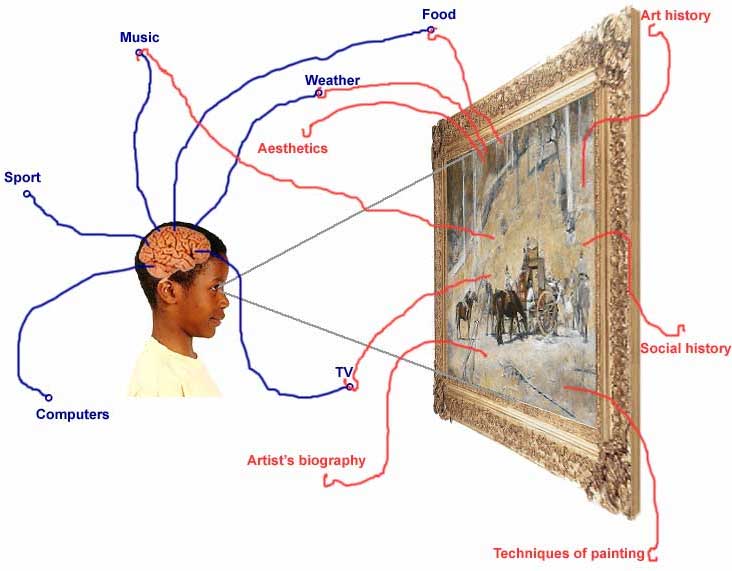

So what happens when a novice visitor confronts an original exhibit? Let us say that the exhibit is a painting in an art museum and the visitor is a 14-year-old boy, who is not even sure why he is there. If one could actually see the process of interaction, it could look something like this:

Stretching out from the boy’s mind are numerous meandering “threads” with a small loop at the tip of each one. These loops are things of interest and meaning to the boy, such as food, music, sport, computer games, television, conflicts with parents and so on. Stretching out from the painting (assisted perhaps by an extended label or a museum educator) are many threads with a hook at the end of each one. These hooks are things that the painting has to offer. Traditionally, these would be aesthetics, art history, the techniques of painting, the social or political history of the period and so on. Is it any wonder that the 14-year-old novice visitor leaves feeling bewildered, feeling that the museum experience had “nothing in it” for him?

What is the solution? Is it to train the visitor to grow new “interest-threads”, so that the painting’s hooks will have something to catch? This is hardly practical; given the above scenario, it is possible, even likely, that he will never return. No, the all-important initial connection, or “personal engagement”, will only occur if there is some way that extra threads can be drawn out of the painting. For example, the museum educator could ask the visitor, “If this painting were a plate of food, what would it taste like? Pizza? Stew? Ice cream? Squashed bananas? …” or “What sport would the person in this painting play? Wrestling? Football? Badminton? Chess? …” At first, such questions may seem to have nothing in common with the painting (in fact, as seen by an art expert, they would probably be seen as “irreverent”), but what they achieve are connections with the visitor’s feelings in indirect ways, by the power of association. This indirectness is important because most people, if asked, “How do you feel about this art work/exhibit?” would find it difficult to respond without cliché or in fact to respond at all. Also, these types of playful, absurd questions bring the art work/exhibit into the visitor’s own world, rather than attempting to achieve the reverse.

Visiting a museum is, for the majority, about (affective) experience, not (cognitive) research. As Allison and Gwaltney observed, in the context of technology exhibitions, ‘Most visitors are collecting impressions and experiences that will “make sense” later in conjunction with other experiences and activities in their lives.’ — Allison and Gwaltney (1991), p. 69. The first step is to help the visitor to actually look at the exhibits because incredibly, most people do not know how to look at an object or image beyond the cursory glance required to either identify or dismiss it (2). The best way to make this happen for a museum visitor is to make the object “their own”.

The task then, is to create a hypermedia exhibit that will give the novice visitor a (positive) affective experience (3). What form would such an exhibit take? According to Alsford, ‘a sequential and relatively highly programmed experience is not unsuitable for [the casual] visitor, and will have its greatest impact at the affective, rather than the cognitive level.’ — Alsford (1991), p. 10. It is true that sequential multimedia exhibits, like many popular films, can be very stirring and emotive (i.e. working at the affective level), but emotiveness is not the same as personal engagement. Emotiveness works on the lowest common denominator and is transient; personal engagement on the other hand, by working at the individual level, has a good chance of “laying roots” and being truly life-enriching.

Thus, if the “open-ended-ness” of personal, affective engagement illustrated above (e.g. “turn this painting into a plate of food”) were to be translated into a computer-based interactive, it would demand, not sequentiality, but serendipity (4). I maintain that, in order for hypermedia to be effective for the novice visitor and (re)gain the sense of playfulness implied by its name, hypermedia developers need to use as a model, not the convergence and certainty of the reference book, but rather the divergence and relative unpredictability of surrealist cabaret (or at least the live floor-talk!).

Footnotes

1. A variation on this assumption is that for novice visitors, visiting a museum is about having an affective experience but that this experience is limited to enjoyment at discovering new knowledge (= cognitive domain).

2. ‘Some art museum educators and curators have accepted, as part of their professional responsibility, the task of helping museum visitors relearn to use their eyes, to see, as well as the more accustomed task of conveying art historical information.’ — Newsom & Silver (1978), p. 77. This assertion, although made in the context of art museums, could apply equally well to general museum education.

3. Incidentally, it is tempting, when trying to stir the visitor’s feelings about a topic, to become too controlling. As Hoekema advises sensibly, ‘Avoid editorialising and excessive cuteness. Do not tell users how to feel about the information, and avoid extraneous or self-conscious humour that distracts from the content. Trust your material, and trust that, if you’ve laid it out effectively, your viewers are genuinely interested in the content.’ — Hoekema (1989).

4. Some other examples include:

Art museum – “This photograph is called ‘The Parade’. Give it three new titles; one funny, one tragic, one strange.” + “Imagine that this sculpture is going to escape tonight. How would it move? Klunk? Slither? Glide? Jog? …”

Historic house – “How would this room change if [Madonna] were living here?” + “How would you change this room if you were living here?”

Geological museum – “Devise a tasty three-course meal for a group of rock-eating aliens.”

Zoo – “Match each of these animals with one of these celebrities.” + ”What sport would each of these animals be best at?”

Transport museum – “How could you turn this bus into a submarine?” + “The nick-name for this kind of tram was ‘toast-rack’. What would be a good nick-name for this truck?”

References

Allison, David K. & Gwaltney, Tom 1991 How People Use Electronic Interactives: “Information Age – People, Information & Technology” Hypermedia & Interactivity in Museums, Archives and Museum Informatics, Pittsburgh, 7–16.

Alsford, Stephen 1991 Museums as Hypermedia: Interactivity on a Museum-wide Scale Hypermedia & Interactivity in Museums, Archives and Museum Informatics, Pittsburgh, 7–16.

Hoekema, Jim 1989 A Manual of Style for Interactive Media, Electronic document (version 1.0) obtained from CompuServe HyperText Forum.

Huston, Mary M. 1990 New media, new messages: innovation through adoption of hypertext and hypermedia technologies, The Electronic Library 8, 336–342.

Newsom, Barbara Y. & Silver, Adele Z. (eds) 1978 The Art Museum as Educator, University of California Press, Berkeley.

Oren, Tim 1990 “Cognitive Load in Hypermedia: Designing for the Exploratory Learner”, in Ambron, S. and Hooper, K. (eds) Learning with Interactive Multimedia: Developing and Using Multimedia Tools in Education, Apple Computer Inc./Microsoft Press Washington, 125–136.