What is it? Where did it come from?

English version of notes for a lecture (in Esperanto) presented at the Universal Congress of Esperanto, Hanoi, Vietnam, June 2012

Video (in Esperanto)

Abstract

Modern art has already been going for more than a century, but even now, many people have serious doubts about it. To address this reputation problem is the first task of this lecture. The second task is to define style in art, in relation to the intention of the artist.

Although modern art first appeared at the beginning of the 20th century, the first seed of it, relativity, started growing in the 15th century, and the second seed, self-sufficiency, in the 19th century. The lecture will explain why modern art would not be possible without these important conceptual changes.

In the multitude of different artistic styles through history there are two main types, which indicate two modalities for viewing, and depicting, the world: the absolute and the relative. An absolutist artwork depicts the world as, according to the artist or the artist’s society, it ‘is’, while a relativist artwork depicts the world as it seems, or appears. A variation of a relativist artwork depicts the world as it ‘feels’ – or, to put it another way, such an artwork depicts the emotional experience of a personal encounter with the world. A second important seed of modern art is the attempt to break the tie between art and the real world, so that artworks stand by themselves. This seed, self-sufficiency, enables abstract (or non-figurative) art.

Modern art’s reputation problem

The two questions of this lecture are “What is modern art?” and “Where did it come from?” But many might ask “Who cares about modern art?” For them it is as if I had asked, “What is the weather on Mars?” or “How do you ferment fish?” Questions not only irrelevant to them, but about something that they actually don’t care for.

So, there should be a third question, before the other two: “Is modern art worthwhile?” That is, is it worth looking at, worth studying, and (possibly) worth buying?

My aim is not that you will like modern art, but that you will at least be more interested in it than you were before.

I work at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (in Sydney, Australia). Every year, since 1921, the Gallery has organised a contest for portrait painting, the Archibald Prize. This year, the award was given to the artist Tim Storrier, for his faceless self-portrait, The histrionic wayfarer (after Bosch) (Figure 1).

This decision caused controversy. Many people said, “This isn’t a portrait. A portrait needs a face!”[1]

In 1973, the National Gallery of Australia bought a painting, Blue poles: number 1, created in 1952 by the American artist Jackson Pollock, for 1.3 million dollars. The purchase of the large, abstract painting[2] not only caused controversy, it caused a scandal. Many people said indignantly, “They call it art?! A young child could make a better picture than that! What a waste of money!” A newspaper at the time had a headline: “Drunks did it!”

In 1959 an edition of the satirical magazine Punch appeared with a comical drawing of a modern artist on the cover. Against the wall were many large abstract paintings, created by pouring and dripping of paint. The artist was upset because his dog, which has just walked through spilt paint, was about to walk on a blank, stretched canvas, lying on the floor. The joke is: “Why is the modern artist upset when a dog messes up the painting? Modern art is so disordered and meaningless that no one would notice the difference!”

Modern art clearly has a reputation problem.

Have you heard the expression “I don’t know much about art, but I know what I like”? I have heard it so many times that it is already clichéd. But people who say it speak the truth. They are saying, in effect, “Maybe, if one studied art and learnt about artists, movements, styles, etc, one would understand and enjoy ‘difficult’ art, but I have a simple, immediate enjoyment of art, and I’m happy with that.”

A definition of style

Many people believe that the two goals of a ‘real’ artist are: firstly, to represent something, and secondly, to make something beautiful. But, although works of art may represent things and be beautiful, the creation of art is about something else. Let me demonstrate:

Imagine that we are all together in an art museum and I am an artist (or at least I consider myself as one). I have decided to create an artwork for the museum. I have a box of junk. I turn it upside-down and the junk falls to the floor (Figure 2).

Now, if we were to go away and leave the ‘artwork’ in the museum and come back a day later, would the artwork still be here? No? Why not? Who would have taken it away? Who has the real power in the art museum? The director? The curators? No, the cleaners! It is they who must decide whether the pile is really a work of art or just junk. So, how would the cleaner decide? And could we make sure that the ‘artwork’ will be here tomorrow? How? A label? A sign? A price tag? A frame?

These objects may be enough, but we probably need something more fundamental, something that would convince cleaners (and others) that this pile of objects is a true work of art, not just that we think it is.

So, we could do something to the junk itself, so that it looked more ‘artistic’, and intentional. We could align the objects. We could choose objects that have similar colours .

We might have ideas, but what would some artists say to us, if they could?

Nora Heysen might say to us, based on her painting, Self portrait (Figure 3): “Emphasise horizontals and verticals. Use mostly neutral colours (browns, greys, creams, black and white) and maybe a small accent of a bright colour, like red.”

The artist William Dobell was famous for his expressive portraits. Based on his portrait of Margaret Olley (Figure 4), he might say to us: “Emphasise curves. Use similar colours, such as creams, yellows and light greens.”

Elioth Gruner was famous for his impressionist landscapes. He might say to us, based on his small painting of a woman on the beach (Figure 5): “Use geometry, even if it seems very subtle.” And, at the same time: “Use atmosphere to blur the boundaries between objects, and reduce the colour differences.”

Eric Wilson was a rarity in Australian art: a true cubist, like Picasso. See the painting in Figure 6. What might he say to us? “Use fragmentation.” In other words, break up the objects and put the pieces together in another arrangement.

So, we could ask advice of any artist. Each would reply to us according to his or her own method of converting chaos into order, of changing chance into intention. And each method is what is commonly called a ‘style‘.

Relativity

But this does not explain why many modern works of art do not look like the real world. Why is there often distortion in modern art? Why is there art now that is completely non-representational – just shapes, lines, colours, etc.?

To solve this problem, we actually have to travel to the fifteenth century.

Figure 7 shows a painting from the city of Siena, in the country now known as ‘Italy’. It is by the artist Sano di Pietro. Note the gold background. Note the Madonna, Mary, in her traditional, ultramarine robe. Note the definite order of the people. And note the strange juxtaposition of the baby Jesus with an adult John the Baptist (in spite of the fact that they were the same age). This means that the reality the artist is depicting is spiritual, not physical.

In short, the picture shows objects not as they seem, but as they ‘are’, according to the society of the time.

Domenico Beccafumi created a painting, 50‐70 years later, with almost the same subject (Figure 8), but look at the differences.

Note the shadow-modelling on the faces and bodies, which helps the illusion of depth. The faces in the Sienese painting are almost flat. Note the surrounding shadows, which hide the details. Note the acidic colours, selected by the artist, not by tradition. The earlier painting has halos, as golden glows around the heads. Does the later painting have halos? Look carefully. Can you see them, floating above the heads as barely visible rings? Why did the artist paint them like this? The artist would have preferred not to depict non-physical things, but, if he must, he decides to paint them as if they were real, physical objects.

The painting of the Madonna of Loreto (Figure 9) by the Baroque artist Caravaggio, around 60 years later, does not depict exactly the same subject as the previous two, but its theme is certainly very similar to those. Note now even more realism, and naturalism: The light and shadows are dramatic. Again, the halos are hovering rings. Note Mary’s bare feet, and the dirty, bare feet of the pilgrim, and the broken wall. These things help us to imagine that this scene is real, not just a mythical story.

From Sano di Pietro to Caravaggio, we see a progression from one approach to another. Sano di Pietro depicts things as they ‘are’, but Caravaggio depicts them as they seemed to him, or according to his experience of and feelings about them. (Yes, the artist did not actually see the events of the Bible, but he used real people as models and drew them.)

The progression is from an ‘absolute‘ to a ‘relative‘ approach.

That is why the invention of perspective in the Renaissance was so important. Finally, artists could represent objects, people and scenes as they appeared, from any angle.

In the twentieth century, many artists continued and stretched the relative approach even further, in many different ways.

For example, the painting of fire haze (Figure 10), painted by the artist Lloyd Rees when he was an old man. Although the details are hidden by the smokey haze (and perhaps by the poor vision of the artist), the colours are anything but hidden.

Relativity was the first ‘seed’ of modern art, and it is the approach of modern art, whether visual (as in the previous example) or emotional (as in the painting Entrance to the seaport of desire (Figure 11), by John Olsen, which is a depiction of the feeling of one man about the ‘wild’ city of Sydney).

Self-sufficiency

But there is another reason why many modern works of art are different to the real world. To find it, let us go to the late 19th century.

Why do so many non-modern paintings have frames? Partly, because a frame (especially a gold frame) makes a painting more showy, more ostentatious, but mostly because a frame around a painting creates a virtual window – which in turn creates an imaginary world, beyond the picture plane. (This is why most modern paintings have very small frames, or even no frame at all.)

The artist who created the painting in Figure 12 (with its huge and very ostentatious frame) certainly does not want us to see paint and brushmarks. Instead, he wants us to see flesh, marble, fur, feathers etc.

The Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky (famous as the first westerner to create entirely non-figurative paintings) saw, as a young artist, a painting of a haystack by the French impressionist, Claude Monet. Later, Kandinsky wrote: “The catalog explained to me that it was a haystack. I could not recognise it. I felt embarrassed at this lack of recognition. I also felt that the painter has no right to paint so indistinctly. I had a dull feeling that the object was missing …. Completely clear, however, was the unanticipated power of the palette, until now unknown to me, which surpassed all my dreams.”[3]

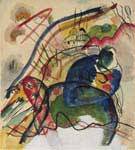

And here is a painting by Kandinsky, from 1913 (Figure 14).

There is no virtual window now, no imaginary world. ‘Paint as illusion’ has truly become ‘paint as paint.’ A work of art can stand on its own.

The second seed of modern art is self-sufficiency.

Paradoxically, the movement which insisted that art must depict real visual sensations was the French impressionism of Claude Monet, but it was French impressionism, with its rough paint and obvious brushstrokes, where one first finds the seed of self-sufficiency.

(By the way, look also at the painting by Monet as an example of relativity. See how light and atmosphere obscure the details, and this was almost 90 years before Bushfire haze at Gerringong by Lloyd Rees.)

Experimentation

So far, we have seen two essential seeds, and features, of modern art: relativity (to represent the world as it seems) and self-sufficiency (to use paint as paint). But there is another feature: the search for something new, something fresh. Since the industrial and scientific revolutions, many artists worry that art is becoming stale, that it is losing its power because of its rules, assumptions and customary ways of doing things. They wonder, “What would happen if I did something unusual, if I deliberately broke the rules?”

One rule, or custom, is to do with how an artist creates.

A usual way for a painter to work is:

• at a vertical, flat surface (a stretcher, which is a sharp-edged rectangle), which is on an easel,

• looking at the object,

• using brushes, and artist’s oil paint on a palette,

• the artist depicts an object, which is the subject of the painting.

Instead, here is the American artist Jackson Pollock, who painted the artwork Blue poles, working (Figure 15):

• The surface is horizontal

• and not stretched,

• The paint is thrown, dripped, flicked,

• the artist is ‘in’ the picture (not looking elsewhere) and…

• the process of creation is the subject of the picture!

Another artist, Hans Hoffmann, once said to Pollock, “You no longer draw from nature, you will stagnate.” Pollock simply replied, “I am nature.”

And what are the ingredients of Pollock’s painting? Not oil paint on canvas, but, for Blue poles: “enamel and aluminium paints with glass on canvas”.

Figure 16 shows a work of art by the Greek artist Jannis Kounellis.

The ingredients are: “steel, wood, plaster, cloth, gas burner, paint and soot marks”. This style is sometimes called ‘arte povera’ (which means ‘poor art’). The name comes from the use of cheap and usually discarded materials.

The border between art and the real world is deliberately unclear. (See the soot on the wall, which is probably a reference to the soot from oil lamps in cemeteries. The wall is now a part of the artwork!)

There is another ingredient in this work of art that may be unique, or at least very unusual: fire!

The creative process as art

One problem, which we still have not solved, is why does so much modern art seems rushed, slap-dash and easy? Let us visit one more painting, by Peter Upward (Figure 17).

Imagine that we are in the studio of the artist, one day in 1961. Imagine in fact that I am the artist.

Welcome to my studio. I’m about to create a big painting. I paint not on canvas, but on board. I put it on the easel, and now I take my palette, paints and brushes and get ready to paint…

Wait a moment… is that right? Can I indeed paint that painting this way? With a small paintbrush? No, no, the brushmarks are too wide!

Did I put the board vertically, on an easel? But the black paint is very thick and lumpy. What would happen if I painted with that kind of paint on a vertical surface? It would drip onto the floor. So, what should I do? I need to lay the board horizontally on the floor, like Jackson Pollock.

And what will I apply the paint with? With a wide paintbrush.

So, now I am ready to paint. I want to create a picture of energy and life, like a dance. I will create a strong mark from ‘here’ to ‘here’.

Oh, my back is sore from over-stretching! And it would be better if I could paint a longer mark with one stroke. This paintbrush should be longer. How? I could tie it to a broom handle. Or, why not get rid of the paintbrush and use the broom instead?

I remove the used board and replace it with another, blank board. (I’ll wipe the used board for another picture.) Now I am really ready. I want a painting like a dance .

So, I paint again. — Hmm. I don’t like the result. Should I fix it with a small paintbrush? No, then I would lose the spontaneous energy of the brushstrokes. No, I must completely start again with a new board.

I get a new, white board and paint again. — Oh no, this is worse than the last one! What to do? I will get a new, blank board and paint again.

Now, imagine that kind of process is repeated five times, but I am still not satisfied with the result. I stop for lunch.

It’s now after lunch, and I have returned to the painting. I try five more times.

I am tired now. Today I will work on another artwork.

Imagine that it is now the next day. I try to make the painting ten more times.

Fast-forward. Imagine that two months have passed. I have made 99 attempts and this is my hundredth attempt.

I paint again. — Yes! That is the painting I’ve been searching for.

So, the important question is: how long did the creation of the final painting take? Less than two minutes, or two months? Or even, the whole life of the artist so far? Truly, an artist cannot create his or her thousandth artwork without finishing 999 works of art beforehand.

Conclusion

Modern art takes many different forms, but it tends to have three qualities, which are:

• relativity – where the artist acknowledges that his or her experience is not necessarily the same as others,

• self-sufficiency – where the artwork, as a thing, can be more important than its subject, and

• experimentation – where the artist wonders, “Why do I have to always do something according to rules or customs? What would happen if I did it differently? ”

This is not a definition of modern art. No one has been able to successfully define “art” (in spite of many attempts), so how would one define “modern art”? My aim was not that you would know exactly what modern art is, and what it is not, or that you would like it. Fortunately, you can appreciate an artwork, even enjoy the experience of thinking about it, without necessarily liking it. If you feel that your appreciation of modern art has grown, even slightly, I will be happy.

Footnotes

[1] In fact, the artist put a likeness of his face on a small piece of paper in the top-right corner.

[2] Viewable at http://nga.gov.au/international/catalogue/Detail.cfm?IRN=36334

[3] Wassily Kandisky, “Reminiscences/Three pictures” (1913) in Wassily Kandisky, Kandinsky: complete writings on art, eds Kenneth C Lindsay & Peter Vergo, Da Capo Press, New York, 1994. p.363

Related

Of toy trains and haystacks: modernism in art: An article from my old website, 1990 (opens in a new window)

Never has so much rubbish been written about my brother Peter Upward’s work. Peter did not paint with a broom or a mop; he painted with a large housepainter’s brush, which you can see in a photo of him in his studio with New Reality on the wall and other paintings. Most of Peter’s paintings were one off. Some he threw away but the description of him painting above is a fabrication and the writer’s fantasy. Peter was influenced by Zen methods of meditation in calligraphy. The lifeforce is in the brushstroke, which is not so prominent in traditional painters’ work. He found some of his direction from John Olsen when John gave him his painting The Procession.

Peter and I grew up in the paintroom behind His Majesty’s Theatre, where our grandfather George Upward designed the stage sets and with 3 men painted the giant backdrops.

You will need to read my biography on Peter, Master of the Dancing Brush, to understand him and his work and some of the idiotic things said about his work.

Penelope Upward, Peter’s sister

Hi Penelope, thanks for taking the time to comment. Yes, you are quite right — much of what I wrote about under the subheading “The creative process as art” was a fabrication. But I wasn’t trying, or pretending, to write an art-historical study of your brother’s painting method. I was trying to demonstrate – especially to those who may be confused or even angry about the apparent rushed, slap-dash and easy qualities of a lot of modern art – that the value of a work of art cannot be judged solely by the amount of time the artist’s brush is in contact with the canvas (or board). Perhaps I should have added a disclaimer to this effect. This article is based on a lecture, where the imaginative, what-if nature of this “fantasy” is, hopefully, more obvious.

Thanks also for that extra information about your brother’s work.

Cheers, Jonathan Cooper