Originally published in Esperanto as La Erotiko de Desegnado in Monato, May 2001

I am standing at an easel in a life drawing group. On either side of me are other people, also at their easels, and in the centre of the room is a naked woman, lying on her left side on a large piece of cloth on the floor. Her left leg, which is tucked up under her right thigh, is coming forward slightly and her raised right arm is lying across the side of her head. With closed eyes, her face is turned a few degrees towards the floor.

After lightly indicating the basic proportions of the pose, I let my eyes wander over her form, looking for things of interest. I notice the curve of the thigh closest to me, as it gently swells and tapers. The shadows from two nearby lamps give the edges a beautiful crispness, fortunately without making them appear hard. With eyes and pencil I slowly and tenderly caress, on paper, the upper contour of her thigh, from the back of her bent knee to her crotch. The lower contour, as it flattens slightly, reveals the contrast of soft, resilient flesh against the harder, cloth-covered floor.

Initially, I was very conscious of the other people in the room. (Would my drawing look clumsy compared to theirs? Was I going to embarrass myself?) But now, caught up as I am in the process, it is as though the model and I are alone in an otherwise empty room.

My eyes move across to the model’s delicately rounded belly.

Contemporary body-fashion dictates that this part of a woman’s anatomy must be absolutely flat; but a real woman, such as the one before me, has a belly which swells gently from her navel, out to her hips and down to her groin. Subtle changes of tone, rather than crisp edges, now define the form. To describe the surface as it advances and recedes, I must hold my pencil at an angle, almost sideways, and press very lightly. In my imagination, each glancing touch of the graphite tickles the model’s flesh, which quivers beneath my fingers. Just as the model and the drawing are merging, so too are my eyes and my drawing hand.

If anyone tells you that drawing a naked model is completely non-sexual, don’t believe them. Actually, drawing a pumpkin or a mountain or a cloud is sexual too, although the connection is not as obvious. There are basically two reasons why drawing is erotic by nature. The first is the three-way sensual connection between the hand (and its extension, the drawing tool), the paper and the subject of the drawing. In no other two-dimensional art form is the tactile element so strong and so direct. “… [L]ine becomes a representation of touch and muscular movement, extending like a caress or redoubling upon itself as a sinuous contraction.” [1] The fact that one of the most common subjects of drawing is the naked human body just adds to this. The second reason is historical. The rise of drawing as an art form in its own right in western art coincides with the move in society from public to private life. In the Middle Ages, many activities which are now performed only in private were done out in the open, in full view. “In their drawings, artists recorded the novel pleasures which were made possible by the extension of privacy. Their drawings could function like a diary, a record of intimate thoughts.” [2]

A recurring theme in drawings has long been everyday, private activities, especially washing or drying the body (or hair). Although the French Impressionists such as Degas eventually made this kind of subject acceptable in European painting, it had been well established in drawing since the 16th century. [3]Looking at such drawings is like spying on strangers. We can feel a voyeuristic thrill, even if the activity we are witnessing is not at all sexual.

Let us return now to the naked model in the room. What is the effect of her looking away from me as I draw her? I wonder: is she aware that I, personally, am staring at her nakedness? Furthermore, if she is aware, does she enjoy it? On the other hand, if she is not, am I violating her by stealing her privacy? This uncertainty, rather than making me anxious, creates a frisson, a kind of exquisite tingle.

It is no secret that life drawing is a very artificial activity. It has well established rules, most of them unwritten, most even generally unstated. As a draw-er I am not supposed to think of the model as I did just then. Instead, I am supposed to think of her as a form to be studied, a collection of surfaces and tones, just as a pumpkin is a collection of surfaces and tones. For her part, the model is expected to think of herself in this way also. To this end, she must virtually leave her own body and cut herself off from the reality of the room she is in. The easiest way for her to do this is to look away, perhaps even close her eyes, and daydream. These expected behaviours and attitudes are supposed to defuse the potential embarrassment of such an abnormal situation. After all, who has never felt a moment of panic in a crowded train or bus when the person sitting opposite, whose face you have found interesting or familiar, suddenly meets your gaze? What do you do? Smile back? No, you very quickly look away and hope that the other person doesn’t realise you were staring. How much more embarrassing if the other person were naked!

So, as long as the model doesn’t look back at me looking at her, it’s OK. After all, she is just an object, isn’t she? Put this way, life drawing sounds rather dehumanising and demeaning. In fact the history of art is full of nude studies where the model was treated purely as an object. Many of these drawings are technically brilliant and certainly deserve our attention. But deep down, we know there is something missing: that feeling of meeting a warm, breathing, feeling person. One artist who managed to transcend this, to draw both the person and the body, was Rembrandt. This very quality is what convinces me—and some art historians—that Figure 1, officially described as ‘School of Rembrandt’, is in fact a work by the master himself.

Seated female nude

Black chalk, corrected with white 16.2 x 12.3 cm.

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

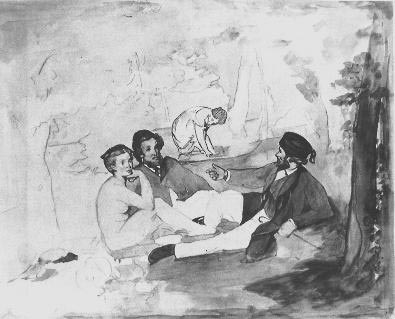

So do models ever look back at the artists who draw them? Before I answer that, let us consider the case of soft-core pornography. It is interesting that men’s magazines make extensive use of the model’s reciprocal gaze, in the form of the ‘come-and-get-me’ look. Here the model looks directly at the camera, lips either pouting or slightly parted, pose indicating her openness and immediate availability. So, what about art? Yes, artists have also used the reciprocal gaze to great effect. One famous example is Manet’s famous Déjeneur sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the grass). The look of the naked woman in this painting, and the preparatory drawing illustrated in Figure 2, is not ‘come-and-get-me’ but instead ‘what-are-you-looking-at?’. It is a look of defiance rather than passivity, of challenge rather than availability. An important extra element in this work is the fact that, while the woman is naked, her male companions are dressed in contemporary clothes. This implies that she is not a pagan goddess or nymph, which would have made her acceptable to polite society, but most likely a prostitute. (Interestingly, the word “pornography” means literally “writing about prostitutes”.)

Les Déjeneur sur l’herbe 1862-63

Pencil, watercolour, pen and ink 37 x 46.8 cm

The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

My drawing is going quite well, I think; it is developing a life of its own. When I began, I had an almost reverential relationship to the model, to those aspects of her form that were unique as well as those which were familiar. But now I regret that I am becoming an unfaithful lover. I have found another object of my attention to compete with her: my own drawing. Ultimately it is the drawing that will tell me when it is finished, not the model. “There is a stage in every drawing when … [its] success or failure … has really been decided. One now begins to draw according to the demands, the needs, of the drawing.” [4]

I must be careful not to overload the image. Up to a certain point, every extra mark makes the erotic process of drawing easier to see; after this point, every extra mark makes it harder. It is a very delicate thing.

Footnotes

1. Maloon, Terence “Intimacy”, in Cooper, Jonathan (ed) Michelangelo to Matisse: drawing the figure Education Kit, Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney 1999

3. It had already been acceptable in Japanese painting and printmaking since at least the seventeenth century.